|

Singing Her World Into Being:

An Examination of William

Osborne’s Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano and

Misogyny in Opera

26 April

2012

William

Osborne composed

Street

Scene for the Last Mad Soprano (1997) for his wife and

professional trombonist

While Osborne and Conant are

both Americans, they have spent the last thirty-two years living and

working in Germany .

They initially moved to

Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano[4] is essentially a musical monodrama for performance artist with computer generated, quadraphonic accompaniment. The performance artist must not only act, but she must also be a proficient singer and trombonist. Street Scene tells the story of an opera singer who lives in poverty on the streets. She is preparing for an upcoming audition, but unfortunately she has nothing to sing. Even though her repertoire is brimming with operatic arias, swan songs, and even challenging trombone excerpts, she has nothing to say. Her life on the street, coupled with her past operatic roles, has thus blurred her concept of reality to the point where she has truly become a fallen woman—the tragic “Mad Soprano.” Osborne suggests that life imitates art, and likewise, art imitates life. Unfortunately, art can sometimes be demeaning, especially towards women, which is true of many operatic works that exude misogynist messages. In Street Scene, the Mad Soprano periodically embodies Lucia from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, Brünnhilde from Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, Mimi from Puccini’s La Bohème, Arianna from Monteverdi’s L’Arianna, and Desdemona from Verdi’s Otello—all in the efforts of trying to find something meaningful to say.

Osborne’s structure for Street Scene alternates between the Mad Soprano’s true identity/reality and the operatic roles that she sings. When the Mad Soprano is her true self, she addresses the audience with words, song, and her trombone playing. Though brimming with chromaticism and accidentals, Osborne’s compositional methods do not reflect the ideas that composers of opera upheld with regard to chromaticism representing the female’s sexual excesses. On the contrary, Osborne employs a dodecaphonic compositional method that makes use of complimentary combinatorial hexachords to represent the Mad Soprano’s humanity.[5] In explaining his method of creating sets of hexachords to represent the characters in his works, Osborne states:

I think of these

cells/hexachords as “crystals” because of the way they interlock.

All of my music theater works are monodramas performed by

Abbie.

For each work, I

select a single type of cell to use, which I think of as the DNA of

the character.[6] In associating complimentary combinatorial hexachords with the organic nature of crystals, Osborne taps into the humanity of his characters. Osborne uses this dodecaphonic method when the Mad Soprano is in reality, and he uses tonality when the Mad Soprano quotes different arias, embodying different operatic characters and entering the dream world of opera. Upon leaving this “alternate reality,” the Mad Soprano comments directly or indirectly on the problems that she sees in this dream world and expresses her hope to create her own dreams, which differ from the patriarchal constructs she is so used to portraying.[7]

The first aria that the Mad Soprano quotes is Lucia’s famous Mad Scene from Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (1835). Based on Sir Walter Scott’s historical novel The Bride of Lammermoor, Donizetti’s opera centers on a tragic love story similar to Romeo and Juliet and the mental breakdown of the “mad” Lucia. In Feminine Endings: Music Gender, and Sexuality, Susan McClary describes this famous Mad Scene:

Lucia displays

her deranged mind without inhibition as she variously relives

erotically charged moments with Edgardo, imagines that they are

exchanging vows of marriage, and anticipates her own death, burial,

and afterlife in heaven.

She has lost touch with outer reality and lives now in a

world made up entirely of the shards of her fears, hopes, and

dreams.[8]

Another maddening aspect of Lucia’s aria is the fact that Donizetti paired her morbid words with a cheerful waltz in E-flat major. Lucia/the Mad Soprano s

Cast on my grave a flower,

But let there be no weeping,

When ‘neath the turf I’m sleeping.

Let not an eye grow dim.[10] Donizetti’s Lucia breaks formal traditions and engages in musical excesses that eventually spill upward into a “coloratura delirium,” which is in complete contrast with the arias of the other characters that conform to typical formal structures and predictable tonalities.[11] Edgardo, the object of Lucia’s infatuation, stabs himself in the final scene of Donizetti’s opera, which can be seen as evidence of Lucia’s contagion. Donizetti not only portrays women as “mad,” but also suggests that they are evil for spreading their madness to others. The Mad Soprano breaks out of her dream world, commenting, “How am I going to sing tomorrow? I’m hoarse! No voice! I’m lost!”[12] The Mad Soprano then finishes her aria as Lucia singing:

For mid the fields of azure

I go to wait for him,

Ah yes, ah yes, ah yes, ah yes,

‘Mid fields of azure I wait for

him,

Ah yes, ah yes, ah yes,

I wait.[13] The Mad Soprano begins and dissolves the aria several times; she even mimes singing the aria, which further emphasizes the fact that she has nothing meaningful to express and that her operatic roles are fully internalized and operate in a psychological world beyond the scope of sound.

The Mad Soprano concludes that perhaps the panel of judges in her upcoming audition would rather hear something original. Osborne employs the use of his derived complimentary combinatorial hexachords to form the melody of the Mad Soprano’s original aria. The Mad Soprano sings to the audience the story of her homeless friend Betty who lives in a box down the street[14]:

I could sing about Betty.

It’s a VERY private story.

My old friend Betty was repairing

her daughter’s bike,

When her husband started

bellowing.

He came out holding some shoes

that she was to have polished.

He couldn’t say what he wanted

because I was there,

So he repeated, “Do you see

these?”

And held them higher and more demandingly.[15] Osborne’s stage directions indicate that the Mad Soprano should end her original aria in a “dark and mystical” tone. The Mad Soprano then abandons her idea and tries to sing Lucia’s aria once more as if scared or startled by the words she just sang. Abandoning Lucia’s aria, she finishes her original aria about Betty:

He said: “My mother never treated

me that ay.”

Betty said: “You don’t need a

mother anymore.”

Brief silence]

And he hit her.

That ended their arguments.

He was much bigger.[16] The Mad Soprano darkly contemplates what she just sang while holding a man’s shoe that she takes out of her bag as if reliving a personal memory—not just recounting a story of a friend.

Abruptly, the Mad Soprano stands and pantomimes holding a spear and shield and walks to center stage where she becomes Brünnhilde from Wagner’s Siegfried (1876) Act 3, Scene 3 singing:

Long was my sleep; I am awake:

who is the Hero who woke me?

Siegfried is it,

he wakes me!

[17]

Brünnhilde was sentenced to remain in a deep sleep for sixteen years after disobeying her father Wotan and using her Valkyrie status to rescue Sieglinde, who was incestuously pregnant with Siegmund’s baby. Brünnhilde’s merciless father stripped her of her Valkyrie status and sent her into a deep sleep, only to be awakened by the kiss of a hero who did not know fear. Ironically, it was the baby, Siegfried, who in turn saved her. The Mad Soprano then comments singing, “Why’s it so easy to sing? Why’s it bubble right up, when you least expect it?” These operatic roles have obviously permeated the Mad Soprano’s mode of self-expression; she cannot just portray these characters—she has to live them. For just like Betty, who was punished for not polishing a shoe, Brünnhilde lost everything and was forced into instigating the end of the world. Wagner’s treatment of Brünnhilde places women in a negative light, suggesting that women who disobey male authorities not only deserve to be punished, but that they should also be burdened with the blame of bringing the world to its end. Catherine Clément comments on Brünnhilde’s role in Wagner’s Ring Cycle:

Entering into

the story of disobedient women who violate the laws proclaimed by

Wotan is the story of the gods as a whole and the end of a world…a

woman alone knows the whole story.

She [Brünnhilde]…has paid dearly, but she still has one more

act to perform: the

lighting of the pyre that will burn a whole people.[18]

The Mad Soprano then transforms herself into the character Mimi from Puccini’s La Bohème (1896), where she sings Mimi’s aria describing her brief and simple life as a seamstress. Puccini’s Mimi suffered a natural death at the end of the opera, dying in the cold from a cough from which she could not recover. She was portrayed as simple and sweet, falling in love with the young Bohemian Rodolfo. But, even the most pure and gentle women will inevitably suffer death in opera.

The Mad Soprano then breaks from her aria and enters back into reality. She sings about her conundrum in not knowing what to sing and considers the possibility of not singing anymore: “But of course, I could NOT sing! And just sit here and be a silent, thinking head. And then I sing and there I am again, suddenly raised to breath and concrete form, no end in sight, thundering along like something real, something visible and solid.”[19] The Mad Soprano clearly links her spiritual existence to her singing and longs for something meaningful and true to express. She then plays virtuosic and waltzing excerpts on her trombone, her other mode of expression. She interjects her playing by stating, “I hope this is leading to something more than my usual collapse!”[20] She concludes this interlude by singing, “I’m not saying we have a lot to sing, but I am saying what we do sing, is not without its problems.”[21] The Mad Soprano is obviously not truly “mad,” for she is able to recognize the misogyny that envelops the operatic roles that she has been trained to sing.

The Mad Soprano then enters the role of Arianna from Monteverdi’s Lamento d’Arianna, singing with eyes closed in a dreamlike state:

Let me die,

and what do you want,

you who comfort me in such a

.harsh fate,

in this great suffering? [22]

Monteverdi’s

L’Arianna

(1607-08)

was commissioned to celebrate a royal wedding in the Gonzaga

court in

Sometimes I think people are

listening…Or am I only imagining?

I thought I heard them breathing.

I just made that up about Betty…It’s really me who’s beaten.

He does it for his—satisfaction.

I don’t remember people anymore. [She stands impassively

looking at the audience.][25] The Mad Soprano briefly bounces back to her role as Mimi, perhaps to distract herself with more lighthearted things like love and flowers, and then she continues her story about her abusive husband as she holds his shoe, “That’s when the plot thickened. She said, ‘You don’t need a mother anymore!’ Took the shoes and dumped them in the frog pond. He didn’t like that.”[26] The Mad Soprano, finally standing up for herself, transitions into the role of Desdemona, another woman who would not cave to her husband’s absurd accusations, singing the “Willow Song” from Verdi’s Otello:

The poor soul that’s pining

alone and lonely

There on the des’late strand.

Oh Willow!

Upon her bosom her head

inclining.

In Verdi’s opera Otello (1887), the “Willow Song,” serves to foreshadow Desdemona’s immanent death. After singing the “Willow Song” and bidding goodbye to Emilia, Desdemona prays before going to bed as a wrongfully accused and innocent woman. Otello then enters her room and tries to force a confession out of her. When Desdemona does not confess to an adulterous act that she in fact did not commit, Otello strangles her to death and commits suicide after his murderous act is discovered. Verdi’s less than subtle implication suggests that women who stand up to patriarchal authority may be punished by death—misogyny at its fullest. The Mad Soprano’s rendition of “Willow Song” perhaps reflects her own fears of being beaten by her husband though she has done nothing wrong, for she says, “It’s getting dark. Tonight, Betty will be beaten.”[28] Osborne indicates in the stage directions that the light slowly fades to darkness with the music. When the light returns, the Mad Soprano is sitting on a bench wiping blood from her hands and mouth with a tissue. She comments that her audition has finally arrived and she will have to tell the judges that her cuts and bruises are just stage make-up, which should be no surprise to her adjudicators since many female characters in opera are beaten by their male counterparts.

After playing an expressive trombone solo, the Mad Soprano bitterly shares her realizations with her imagined public, “Sometimes they look at me, and sometimes they applaud… like when watching pigeons. They feel better for it, then walk on. It’s not art. It’s a question of…entertainment.”[29] Osborne describes the Mad Soprano’s alienation from her “own” patriarchal society:

…The roles she must sing are not

only utterly demeaning, but that more often than not, artistic

expression is reduced to being mere entertainment for a society that

has little cultural sensibility left—sexist or not.

The pedestrians applaud for her as if she were doing tricks.

Or they stand and stare because they think she is dead.[30] In a moment of panic and frustration about still not having any material to sing for her audition, the Mad Soprano declares, “Do you know what it means to be without a song? People will step on you.”[31] Despite the Mad Soprano’s struggle against the marginalization of the humanity of women throughout the entire work, she is able to re-gather her composure and concludes the work by singing her own heartfelt dreams:

Tomorrow night the lights will

rise,

Floating by themselves in Love’s

order.

And far from this corner on the

street,

We’ll sing from our hearts.

You and I. We’ll sing

from our hearts.[32] Osborne’s Street Scene ends with a glimmer of hope in that the Mad Soprano finally formulates her own dreams. The Mad Soprano never fully submits to the prophecies of her ingrained operatic roles of Lucia, Brünnhilde, Mimi, Arianna, and Desdemona. Modern society glorifies operatic traditions dating back over four-hundred years, despite fundamental philosophical flaws rooted in misogyny. Osborne and Conant’s new genre of chamber music-theater opposes many operatic traditions such as over-the-top scenery, large casts, potentially obstructive texts, and general spectacle. Street Scene is one of nine of Osborne’s works in the chamber music-theater genre, which were developed to explore the world of a single character. This sense of character is further represented by Osborne’s own method of deriving complimentary combinatorial hexachords that musically create a character’s DNA. Osborne poignantly summarizes the cultural effects that Street Scene and his other chamber music-theater works hope to produce:

The true identity of women in

society will be formulated only when they are allowed to be artists

and determine for themselves who they really are.

As women find their true place in our culture, we will obtain

not only a greater freedom and dignity, but also a fuller and more

balanced understanding of human consciousness.[33] Osborne and Conant have created new musical traditions, both formally and philosophically, that reject the implications of misogyny and enable women to find truth as expressive artists. These new musical traditions will allow women to thrive amid “the wasteland,” but they may even transcend their current place in society.

Appendix I

Excerpts of Emails Between William Osborne to Jessica Ducharme,

March 27 and 28,

2012.

March

27, 2012, Jessica Ducharme wrote:

In a lot

of the reading that I have done, scholars make the connection

between a woman singing with extreme chromaticism-- musically 'out

of the box'-- with her eroticism or overt sexuality (which must be

punished!). In looking at your score for Street Scene, I can't help

but notice the chromaticism in both Abbie's part and the

accompaniment. Are there any correlations between your choosing to

use chromaticism and the chromaticism in opera? Or, is your use of

chromaticism just a characteristic of your modern composition style?

I remember you mentioning some time ago that you sometimes compose

with hexachords and sets-- any cultural associations to be made

there?

March

28, 2012, William Osborne responded:

The

tonality/atonality binary isn't very relevant to my work.

My music is basically dodecaphonic though with strong tonal

implications.

If

anything, I do just the opposite of what you mention.

I use tonality as a step outside of reality.

In Street Scene, the arias she quotes are tonal and convey

her entering into the dream world of opera.

She then comments, directly or indirectly, on the problems

she sees with that dream world and expresses her hope to create her

own dreams.

I will

try to put something together soon about my use of hexachords --

something that I should have done 30 years ago.

The hexachords are comprised of 3 notes cells which I think

of as the DNA of the characters I create.

I also associate them with crystal structures.

I'll try to make some diagrams to explain why.

People forget how much organic matter is crystaline, like

sugar or tree sap.

More

about all of this soon, or so I hope.

Appendix II

William Osborne’s “Cell Theory”

as used in Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, emailed to Jessica

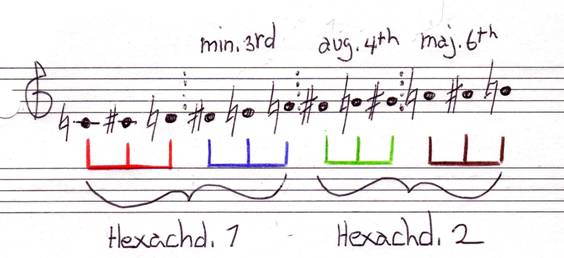

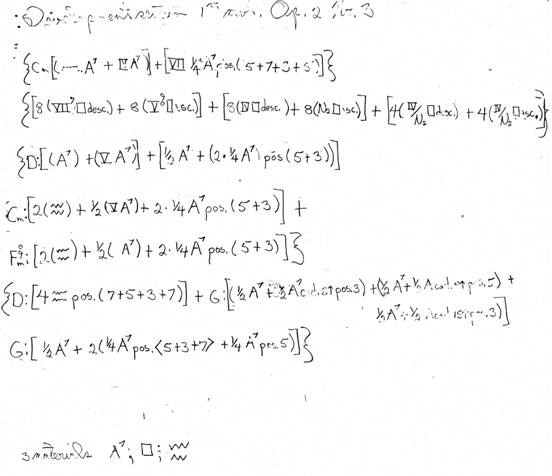

Ducharme April 16, 2012. (pp. 16-20): A combinatorial cell is three notes that when transposed can produce all 12 notes of the octave. For example, a cell made of three half steps like C-C#-D, can be transposed up a minor third, an augmented fourth, and major 6th to produce all 12 notes, as in the diagram below:

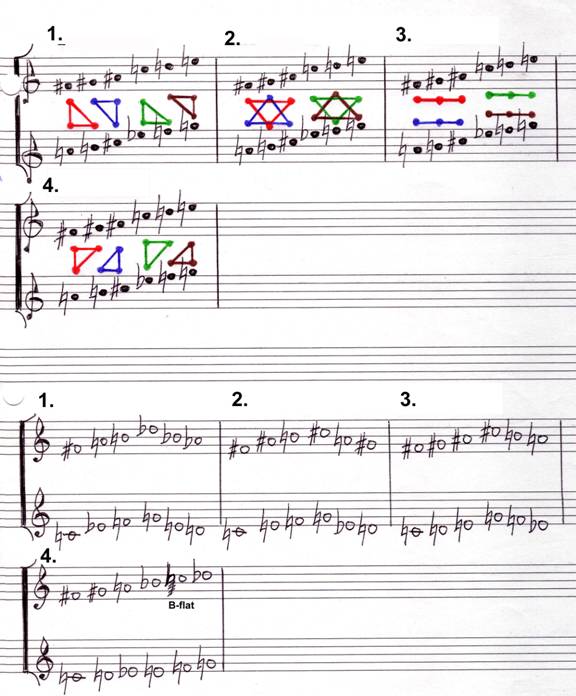

The diagram below shows how I derive combinatorial cells. I found that if I line up two whole tone scales a minor third apart (one starting on F# and one on A-natural as in the diagram below) I could draw triangular patterns between them to produce more combinatorial cells. Not any triangle will do. They must be the same shape and mirror images of each other. For example, you can look at the red triangle in number 1, and then see the notes it outlines written out in the third staff in the diagram. The blue triangle (which is the same shape and mirror image) makes the other three notes to form a hexachord. Numbers 2 through 4 show how different shaped triangles produce different cells/hexachords.

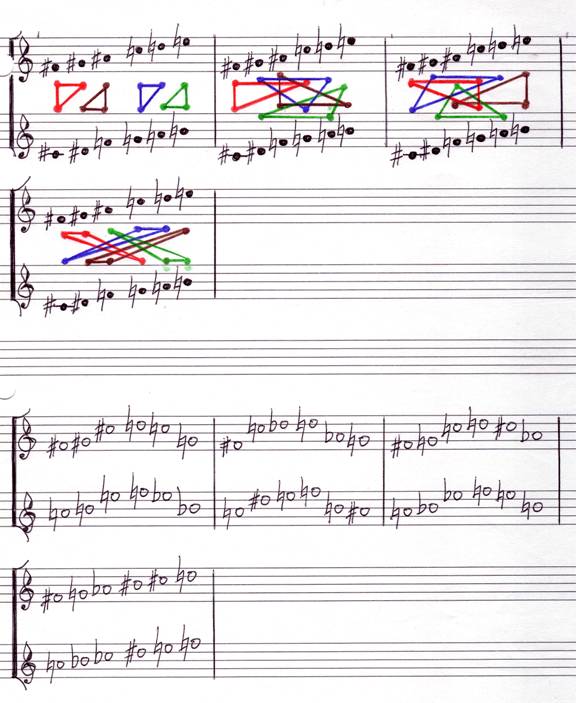

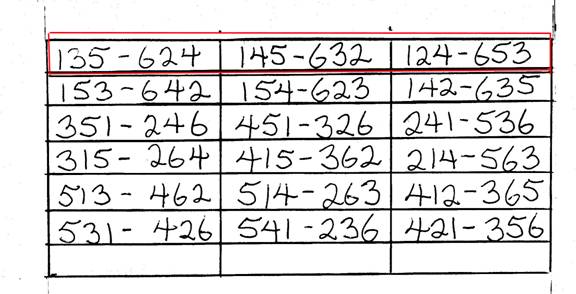

I think of these cells/hexachords as “crystals” because of the way they interlock. Almost all my music theater works are mono-dramas performed by Abbie. For each work, I select a single type of cell to use, which I think of as the DNA of the character (except for Aletheia, our most recent work, which mixes various cells.) I also found that I could mutate the cells by symmetrically exchanging its notes with its mirror cell in the hexachord as shown in the numbers enclosed in the red box below. For example, the 135-624 in the first column is transformed to 145-623 in the second column by having 3 and the 4 exchange sides in the hexachord. And in the third column 2 and 5 exchange sides. In addition, the order of the notes in each three note cell can be permutated. For example, in the first column we see the permutations of 135, 153, 351, 513, 531. And the same for 624, and so on. So the hexachords can exchanges notes between their cells, and each of those cells can mutate their order. Each cell has six permutations, and each of the hexachords those cells produce can symmetrically exchange notes. The chart below shows how one six note combinatorial hexachord can produce 18 permutations – or mutations to continue the biological analogy And of course, those 18 hexachords each have 12 transpositions in an octave, so the “genetically unified” material they produce is very extensive and can be used to create a character.

So that’s my cell theory in a nutshell. I’m sure you’re utterly confused. We could go over it this summer and it would be a lot easier to make clear. I could also show you how the cells appear in the music and play examples. Another even more idiosyncratic technique I use is that I have developed a way of notating the structure of sonata allegro form using something like algebraic formulas. Below are the formulas for Beethoven’s Op. 2. No. 3 (a piano sonata.) I sometimes use these formulas in our theater works, such as for the “overture” of Street Scene. It is a kind of sonata allegro form but played by sirens. Aletheia makes extensive use of this technique throughout the work. Perhaps we can go over this someday if you write your dissertation about our work. It is difficult to explain in text, but easy to demonstrate in person. I developed this method when Abbie and I were students. We also used it to write some solo trombone works and Music for the End of Time. Anyway, here are two examples of the formulas. I create the genetic material with the cells, and give them form with these formulas.

Bibliography

Ammer,

Christine.

Unsung: A History

of Women in American Music.

Bianconi,

Lorenzo.

Music in the

Seventeenth Century.

Clément,

Catherine; translated by Betsy Wing, forward by Susan McClary.

Opera, or the Undoing of Women.

Cusick,

Suzanne.

‘There Was Not One

Lady Who Failed to Shed a Tear’: Arianna’s Lament and the Construction

of Modern Womanhood. “Early Music,” Vol. 22, No. 1, Monteverdi II

(Feb., 1994), pp. 21-43.

Diamond,

Beverly and Moisala, Pifkko.

Music and Gender.

Donington,

Robert.

The Rise of Opera.

Drinker,

Sophie.

Music and Women, The

story of women in their relation to music.

Duke, C. A.

A performers guide to

theatrical elements in selected trombone literature.

Ewen, David.

The New Encyclopedia of the

Opera.

Foucault,

Michel.

Madness and

Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason,

trans.

Richard Howard.

Grout,

Donald Jay.

A Short History of

Opera: One-Volume Edition.

Laing,

Heather.

The Gendered Score:

Music in 1940s Melodrama and the Woman’s Film.

Lamay,

Thomasin (editor) et al.

Musical Voices of Early Modern Women, Many-Headed Melodies.

McClary,

Susan.

Feminine Endings: Music

Gender, and Sexuality.

Mordden,

Ethan.

Demented: The World of

the Opera Diva. Osborne,

William; Conant, Abbie.

www.osborne-conant.org,

2012.

Palisca,

Claude V.

The Florentine

Camerata: Documentary Studies and Translations

(Music Theory

Translation Series).

Randel, Don.

The New Harvard Dictionary of

Music.

Schrade,

Leo.

Monteverdi: Creator of

Modern Music.

Showalter,

Elaine.

The Female Malady:

Women, Madness, and English Culture, 1830-1980.

[1] Osborne,

William.

You Sound

Like a Ladies Orchestra: A Case History of Sexism Against

[2] Ibid. William Osborne: Artist and Activist: an Interview of William Osborne With Catherine J. Pickar, As Published in the IAWM Journal. < http://osborne-conant.org/iawmint.htm> Accessed March 9, 2012 [3] Ibid. Miriam and Our Theories on Chamber Music Theater. < http://www.osborne-conant.org/miriam-video.htm#essay> 2011. Accessed March 7, 2012

[4]

[5] See Apendix II [6] Osborne, William. As quoted in an email to Jessica Ducharme. March 28, 2012. See Appendix I for full text. [7] Ibid. [8] McClary, Susan. Feminine Endings: Music, Gender and Sexuality, p. 92. [9] Audio example no. 1 [10] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, p. 3, rehearsal no. 9. [11] McClary, Susan. Feminine Endings: Music Gender, and Sexuality, p. 92. [12] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, p. 4. [13] Ibid., 5. [14] Audio example no. 2 [15] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, 9. [16] Ibid., 11.

[17] Osborne, William.

Street Scene for the

Last Mad Soprano, p.11, rehearsal no. 32.

Original German text sung:

“Lang war mein Schlaf; ich bin erwacht: wer ist der Held, der

mich wer erwecht? Siegfried ist es, der

[18] Clément, Catherine. Opera, or the Undoing of Women, 139. [19] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, 14. [20] Ibid., 19. [21] Ibid., 21.

[22] Osborne, William.

Street Scene for the

Last Mad Soprano, pp. 21-22, rehearsal no. 53.

Original Italian text

sung: Lasciatemi morire! E chi volete voi che mi conforte in

così dura sorte, in così gran martire? “

[24] Ibid., 23. [25] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, p. 23, rehearsal no. 56. [26] Ibid., 24. [27] Ibid., p. 25, rehearsal no. 62. [28] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, 26. [29] Ibid., 29. [30] Osborne, William. http://osborne-conant.org/Street.htm, 1997. Accessed March 15, 2012. [31] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, 32. [32] Osborne, William. Street Scene for the Last Mad Soprano, 33. [33] Osborne, William. http://osborne-conant.org/Street.htm, 1997. Accessed March 15, 2012.

|