|

|

|

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Osborne

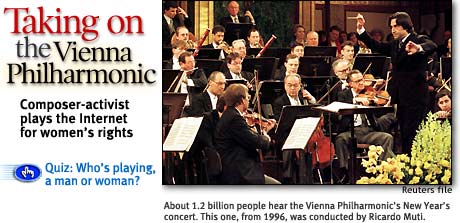

challenged the Vienna Philharmonic’s all-male sexism - and provided the intellectual underpinning for street protests at Carnegie Hall in New York. |

THROUGH HIS ADROIT and impassioned use of the Net, William Osborne

mobilized a tiny, far-flung band of feminists who pressured the Vienna Philharmonic — among

the world’s highest-paid orchestras and, historically, the most important

in terms of symphonic music — to accept a woman member for the first time

since it was founded in 1842. Osborne, who has lived in Germany for the past 19 years, not only challenged the Vienna Philharmonic’s traditional all-male ideology; by disseminating detailed scholarly articles about the orchestra’s operations on the World Wide Web, he provided the intellectual underpinning for street protests at Carnegie Hall in New York and caught the attention of the traditional media — the very catalysts that led to the hiring of harpist Anna Lelkes in 1997. |

||||

| William Osborne |

Cybergrass — Osborne’s term

for grassroots activism in cyberspace — is neither new nor limited to the

cultural arena. In the world of finance, disgruntled shareholders have

organized via the Internet to influence bankruptcy negotiations; labor

unions have seen rank-and-file rebellions fostered on the Net. But Osborne

vs. the Vienna Philharmonic provides a fascinating, even unique, case

study in the annals of musicology and the wider world of grassroots

activism. Cybergrass — Osborne’s term

for grassroots activism in cyberspace — is neither new nor limited to the

cultural arena. In the world of finance, disgruntled shareholders have

organized via the Internet to influence bankruptcy negotiations; labor

unions have seen rank-and-file rebellions fostered on the Net. But Osborne

vs. the Vienna Philharmonic provides a fascinating, even unique, case

study in the annals of musicology and the wider world of grassroots

activism.‘ART IS JUST AN EXCUSE’ More than three years ago, in “Art Is Just an Excuse,” the first of several seminal essays, Osborne contended that the Vienna Philharmonic’s belief in male supremacy was gender bias of the worst sort, rooted in a historical rationale of national identity and cultural purity, and that its exclusionary policy was part of an intolerable racist heritage. The orchestra’s discriminatory practices, he argued, cast such a pall over its considerable artistic achievement that the institution has turned out to be the shame, not the pride, of Western civilization. |

||||

.

With this argument, Osborne and his

cohorts ignited a global debate in cyberspace. Classical music fans from

New Zealand to Costa Rica traded thousands of e-mail messages, for and

against; some suggested further action (a boycott of Vienna Philharmonic

recordings by music libraries, for instance), while others dismissed the

concern over gender bias as kowtowing to political correctness. The

intensity of the debate was as striking as it was widespread. .

With this argument, Osborne and his

cohorts ignited a global debate in cyberspace. Classical music fans from

New Zealand to Costa Rica traded thousands of e-mail messages, for and

against; some suggested further action (a boycott of Vienna Philharmonic

recordings by music libraries, for instance), while others dismissed the

concern over gender bias as kowtowing to political correctness. The

intensity of the debate was as striking as it was widespread.When news of the debate seeped into print and onto radio and television in Europe and the United States, it was deeply embarrassing to the more progressive members of the private, self-governing orchestra, but especially to the Austrian government, which employs the 150 or so Vienna Philharmonic players as civil servants in the Vienna State Opera orchestra, a separate, publically funded, nearly identical twin. If bad publicity was the lever that pried open the Vienna Philharmonic to women, it was Osborne’s advocacy in cyberspace that picked the lock to the door. ‘POWERLESS WITHOUT THE NET’ “We would have been powerless without the Internet,” says Osborne, 47, a gangling New Mexico native with pale blue eyes and a reddish goatee. He noted in a recent interview that the core group of feminists who actually organized the protest numbered fewer than a half-dozen. |

|||||

.

Chief among Osborne’s allies were

Monique Buzzarte, a New York freelance musician and writer who put up a Zap the VPO Web

site to encourage and track the protest, influencing the National

Organization of Women to get involved, and Varda Ullman Novick, a Los

Angeles media researcher and pollster who acted as a traffic catalyst,

instigating debate by forwarding e-mail messages to key music list

servers. .

Chief among Osborne’s allies were

Monique Buzzarte, a New York freelance musician and writer who put up a Zap the VPO Web

site to encourage and track the protest, influencing the National

Organization of Women to get involved, and Varda Ullman Novick, a Los

Angeles media researcher and pollster who acted as a traffic catalyst,

instigating debate by forwarding e-mail messages to key music list

servers.“Actually, the Vienna Philharmonic couldn’t have cared less about us,” Osborne adds. “What we say doesn’t count. It’s what the New York Times says that counts. The most important thing was to use the orchestra as a clear illustration of how reactionary classical music is. If it were just the Vienna Philharmonic, the whole issue would be much too parochial to bother with. “The real issue, which the orchestra validates, is that women are not treated fairly in music,” he says. “I wanted to show that we’re not just talking through our hats, that this is a really important problem. In a certain way, taking on the Vienna Philharmonic is a means to a bigger end. I couldn’t care less about Viennese parochialism. That’s a backwoods place, Vienna, if you want to know the truth. I’m trying to focus on classical music at the end of the 20th century.” POWER AND INFLUENCE Parochial or not, the power and influence of the Vienna Philharmonic is evident 157 years after it gave its first concert as an ensemble (then called the Philharmonic Academy) to present what was at the time a new genre of post-Beethoven symphonic music. Today, the Vienna Philharmonic not only commands the highest concert fees of any orchestra — as much as $200,000 a night, and sometimes more, on standing-room-only international tours — it sells more recordings and earns more money for its members than any other orchestra, except perhaps for the Metropolitan Opera orchestra. Its reported annual income amounts to about $15 million after expenses, income divided among the 150 players. In addition, Philharmonic members earn large government salaries for their jobs in the Vienna State Opera orchestra, and a significant minority earn yet a third salary, also government-paid, to teach at the Vienna Music Academy. LONG, BITTER EXPERIENCE Part composer, social historian and musicologist, Osborne came to the issue of gender bias through long and bitter experience. For many years, he and his wife, Abbie Conant, a classical trombonist, fought sexism in the Munich Philharmonic. Their court battles with that orchestra, following Conant’s arbitrary demotion from solo to second trombone, ultimately ended in a precedent-setting legal victory — but not before she struggled “through some of the worst experiences of my life,” she says, “simply because I was a woman trombonist.” |

|||||

. .

Osborne had tried spreading the word about gender bias in Munich with paper mail. “It was so laborious,” he recalls. “And then I got a modem — and boy! I really started spreading the word. Instead of standing in line at the post office, all I had to do was type something up and hit a button.” |

|||||

|

|

Building on his Munich experience, Osborne posted his first Internet

message about the Vienna Philharmonic on Oct. 16, 1995. The detailed note

described the orchestra’s belief that “gender and ethnic uniformity give

it aesthetic superiority.” Sent to a list of American trombone and trumpet

players, the message received little notice; but four days later it was

forwarded to the International

Horn Society, where it caused extensive discussion. Within two weeks,

e-mail traffic amounted to 50 pages of printouts. USING THE INTERNET “At that point,” Osborne says, “I began using the entire music area of the Internet [list servers, news groups and chat rooms] to try to raise a protest.” On Jan. 24, 1996, he sent documented information about the orchestra’s categorical exclusion of women to various music lists: Gender in Music, the International Alliance for Women in Music, the International Trombone Association, the IHS, and various trumpet, tuba and brass groups. His information was forwarded separately to the lists of the International Conference of Symphonic Musicians, the American Musicological Society and others, for a total of 11 groups that he knew about. Later he learned that feminist, opera and labor-relations organizations also got the information, causing e-mail discussion (especially at ICSOM) that continued unabated for months. Another Osborne post (“More VPO Info”) followed, encouraging gender-in-music scholars to begin writing about sexism in the Philharmonic and other orchestras. He contended — correctly, as it turned out — that reporters in the traditional mass media would take notice. He also urged members of Gender in Music to write the orchestras themselves, and he supplied addresses. Yet another significant post (“Orchestras and Social Reality”) went to the IAWM and seven other lists on Jan. 31, 1996. “It was not specifically about the Vienna Phil, but rather about what people could do to oppose discrimination,” Osborne notes. Relentless as ever, he wrote largely in response to questions that had been raised in the e-mail discussions but hadn’t been answered. This time he drew a direct link to the case of Conant vs. the Munich Philharmonic, using it as a concrete example of a successful action. IMPACT IN REAL WORLD Within days, on Feb. 2, 1996, he received his first e-mail inquiry from a journalist, Andreas Saenz of La Nacion in Costa Rica, who proposed writing an article. “Saenz did the piece and predicted protests against the Vienna Phil more than a year before they actually happened,” Osborne says. “He based his prediction on the activity that was evolving on the Internet.” Osborne soon began to see the impact of his cybergrass campaign in the real world. On Feb. 13, 1996, West German State Radio interviewed members of the Vienna Philharmonic to get their views on the growing controversy. What they said in defense of the orchestra’s exclusionary policy merely confirmed Osborne’s critique. “From the beginning,” flutist Dieter Flury explained, “we have spoken of the special Viennese qualities, of the way music is made here. [It] is not only a technical ability, but also something that has a lot to do with the soul. The soul does not allow itself to be separated from the cultural roots that we have here in central Europe; and it also doesn’t allow itself to be separated from gender. “So if you think the world should operate according to quotas,” Flury went on, “then it’s naturally irritating that we’re a group of white-skinned male musicians that exclusively performs the music of white-skinned male composers. It’s a racist and sexist irritant. I believe you have to put it that way. If you establish superficial egalitarianism, you lose something very significant. Therefore, I’m convinced that it is worthwhile accepting this racist and sexist irritant, because something produced by a superficial understanding of human rights would not live up to the same standards.” If that wasn’t clear enough, Roland Girtler, a professor of sociology at the University of Vienna, added: “Another important argument against women is that they can bring the solidarity of men into question. You find that in all men’s groups. And the women can also contribute to creating competition among the men. They distract men.” THE PROTEST BEGINS Osborne lost no time exploiting such remarks. He transcribed and translated that radio interview, and posted the transcript on the Internet in both English and German. This prompted the IAWM, an organization largely comprising female academics and composers, to begin formulating a protest action. Much discussion centered on possibly using the street-theater tactics of the Guerrilla Girls, a New York-based artists’ collective whose anonymous members don gorilla masks in their actions. Osborne demurred. “Most people are not aware of the Vienna Philharmonic’s employment policies,” he wrote in a May 14, 1996, e-mail. “A simple and dignified protest by women musicians in front of the concert halls during the orchestra’s international tours, along with factual advance letters to the media, would be all that it takes to create a lot of publicity.” Ten months later, in the weeks leading up to and during the orchestras’s winter tour of the United States in February and March of 1997, events would prove him correct. In the meantime, he continued to prepare the ground, teaming up with Monique Buzzarte, who had been reading Osborne’s Internet messages. As she followed the e-mail debate, Buzzarte recalls, she was struck by a message from one of the IAWM leaders saying it wasn’t the group’s role to get involved in an orchestra protest. “That made me go ballistic,” she recounts. “It was like a leader of the NAACP saying it shouldn’t get involved in civil rights.” Buzzarte sent a stinging reply to that effect and volunteered to help coordinate any effort that might be initiated. “It sealed my fate,” she says. “The IAWM made me a board member and allocated about $300 for me to do something. You can’t even do postage with that. So I thought the best thing was to use the power of the Internet and mass-forwarding.” ZAPPING THE VPO Buzzarte set up her provocative, highly organized ZAP the VPO Web site, launching it on Nov. 15, 1996, with service instructions (“What can I do?”), background information (“Who’s taken a stand?”), dates and places for demonstrations, a news archive of media coverage and an online library, as well as links to other music- and government-related Web sites and mailing lists. She wrote prominent musicians and feminists — “Anybody I knew or thought I could get hold of by e-mail” — asking for a statement of solidarity. “They were just b-flat requests: ‘Here’s what I’m doing. I’m soliciting comments that I can parlay; I will post your response on my Web site.’” Her campaign, dubbed VPO Watch, also displayed a sense of humor in the use of such slogans as “Testosterone Is Not An Instrument” and “Don’t Let the Men of the Vienna Philharmonic Keep Playing With Themselves.” |

||||

.gif) .

The first to send a statement was

the noted avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros; eventually Gloria Steinem

and the composer Joan Tower responded. Only a small number of established

artists and feminists replied, however. “That was an eye-opening

experience for me,” the 38-year-old Buzzarte says. “I guess I’m an

idealist. It hadn’t really occurred to me that people with big reputations

who didn’t have to be scared would want to keep their distance.” .

The first to send a statement was

the noted avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros; eventually Gloria Steinem

and the composer Joan Tower responded. Only a small number of established

artists and feminists replied, however. “That was an eye-opening

experience for me,” the 38-year-old Buzzarte says. “I guess I’m an

idealist. It hadn’t really occurred to me that people with big reputations

who didn’t have to be scared would want to keep their distance.”Having done the spadework, Osborne now unleashed his main Internet attack: an unrelenting series of well-reasoned, historically detailed, acutely researched articles notable for their scholarly tone and, in contrast to the ZAP the VPO Web site, the absence of polemics. In all, he posted a half-dozen articles and thousands of e-mails amounting to tens of thousands of words over a period of roughly 2 1/2 years from October 1995 to June 1997. Buzzarte not only put all his essays and articles on her Web site, she posted the news articles that began appearing in the print press. More than 125 articles were published from Jan. 15, 1997, to Feb. 28, 1997. The first came out on the front page of Der Kurier, an important Austrian daily in Vienna, under the headline: “US Womens’ Groups Theaten Boycott of the Philharmonic / Massive Pressure on the Orchestra to Take Women Musicians.” Within six weeks more than two dozen major newspapers around the world reported that the orchestra had voted reluctantly to accept its first woman. |

|||||

| Monique Buzzarte, creator of

the Zap the VPO Web site. |

A majority of those articles

came on the eve of the Vienna Philharmonic’s 1997 American tour, and

another 75 appeared in the aftermath of the historic vote “on the woman

question” (bitter words of the orchestra’s then-chairman Werner Resel, who

opposed the vote and soon resigned). A majority of those articles

came on the eve of the Vienna Philharmonic’s 1997 American tour, and

another 75 appeared in the aftermath of the historic vote “on the woman

question” (bitter words of the orchestra’s then-chairman Werner Resel, who

opposed the vote and soon resigned). Most of the press reports contained information and ideas traceable to Osborne’s original e-mail messages and article postings. During that same six-week period, traffic on the ZAP the VPO Web site was astonishing by the standards of classical-music groups, if not by the Internet’s. Buzzarte doesn’t know exactly how many people logged on — “I stopped counting after 10,000 hits,” she says — but she estimates enough people visited her site to fill 5,000-seat Carnegie Hall many times over. Which is just the sort of thing that would concern the Vienna Philharmonic or any major touring orchestra, Osborne maintains. HISTORIC VOTE |

||||

| The historic

vote to admit a woman came on Feb. 27, 1997, the same day that the

orchestra flew off to the United States to play at Carnegie Hall.

|

It was no coincidence, he adds, that the historic vote to admit a

woman came on Feb. 27, 1997, the same day that the orchestra flew off to

the United States to play at Carnegie Hall. (In its only other U.S. stop

on that tour, the Vienna Philharmonic played three concerts at the Orange

County Performing Arts Center in Costa Mesa, Calif., where about 150

protestors demonstrated.) Perhaps not surprisingly, the battle for public opinion of the New York intelligentsia matters as much to Osborne as it does to the orchestra. “In fact, it’s more important to change the thinking of the New York Times — and therefore the thinking of the New York intelligentsia, which reads it faithfully — than to change the Vienna Philharmonic. “Columbia Artists, the agency that controls something like 95 percent of the world’s name conductors, is headquartered in Manhattan,” Osborne continues. “That says something about why the Vienna Phil, which uses only guest conductors, cares what the New York Times says. It’s basically the only paper they [the orchestra] read from America. And it’s not so much that they go to America as to Carnegie Hall.” Despite demonstrations in front of Carnegie Hall for three consecutive years however — never large, the turnouts dwindled from 80 or so protestors in 1997 to eight in 1999 — the Vienna Philharmonic continued to play sold-out concerts. And while the New York Times had reported the admission of the harpist Anna Lelkes into the orchestra as front-page news, its music critics did not take the issue of gender bias seriously. In a 1997 column, the Times chief music critic Bernard Holland dismissed the protest with a condescending brush-off. His disdain was palpable. “What we seem to be witnessing,” he wrote, “is a clash of two provincial capitals.” In his opinion, the issue was a mere misunderstanding between insular, old-fashioned, but respectable keepers of tradition in Vienna and newfangled, impatient, Southern California hicks in Culver City (where the then-president of the IAWM lived). “Culver City may have a hard time understanding that the values so immediately important to it may not be important to the Viennese, even to many of its women,” Holland wrote. It was the same unction the orchestra used to excuse itself. The following year, when the orchestra arrived in New York (on the first anniversary of Lelkes’s hiring), the Times’s classical music editor James R. Oestreich interviewed Resel’s replacement, the new orchestra chairman Clemens Hellsberg, and took at face value Hellserg’s claim that the orchestra was now committed to hiring women. Oestreich gave considerable legitimacy to the claim that gender discrimination was a thing of the past, even though the orchestra had just filled four jobs in the string and brass sections with men again, instead of with women. The orchestra had not only failed to hire a woman but, as reported in the Los Angeles Times, had declined to audition a highly qualified female candidate for solo viola. (She was Vienna Academy-trained violist Gertrude Rossbacher who had played for 10 years in the Berlin Philharmonic, where she’d been hired by its legendary conductor Herbert von Karajan. The Vienna orchestra filled the solo viola position with a male second violinist, not a regular viola player, from the Vienna State Opera.) SECOND WOMAN HIRED |

||||

| ‘The Vienna

Phil is trying to present this as a big step forward. But hiring women

harpists is nothing new. Male harpists are rare.’ — WILLIAM OSBORNE |

On the eve of the 1999 tour, as though to lend credence to the New

York Times’s reporting, the orchestra announced it would hire a second

women, Julie Palloc, another harpist. She will join the orchestra this

year, when Lelkes is expected to retire. “The Vienna Phil is trying to present this as a big step forward,” Osborne says. “But hiring women harpists is nothing new. Male harpists are rare. Lelkes played for more than 20 years with the orchestra as a permanent subsitute, without being granted membership in the club. She earned less pay and her name never appeared in the programs. She was a non-person.” In any case, female harpists do not figure in the central equation of the orchestra’s psychology or its music-making. As second violinist Helmut Zehetner told a German interviewer: “If you ask how noticeable gender is with these colleagues, my personal experience is that this instrument is so far at the edge of the orchestra that it doesn’t disturb our emotional unity.” For the first time, however, a New York Times critic, Anthony Tommasini, took serious notice of the orchestra’s sexism by reviewing its 1999 Carnegie Hall concerts in the context of Osborne’s charges, rather than treating gender bias as a moral issue wholly separate from art. Without naming Osborne, he quoted from one of Osborne’s IAWM articles and, while still praising the quality of the playing, endorsed the view that the orchestra’s continuing sexism is wrong artistically as well as ethically. ‘MAKES NO SENSE’ “Obviously, the unanimity of purpose that the Vienna Philharmonic has achieved is a precious thing and you can understand their fear of diluting it,” Tommasini wrote. “But what accounts for this quality? The maleness of the players? Maybe that was so in a time when women routinely were oppressed, but it makes no sense any longer.” When Tommasini’s review appeared, Osborne was jubilant. “So finally we got the truth into the New York Times,” he e-mailed associates. “The Times’s previous dismissal of your protests played a large role in bolstering the orchestra’s resistance to change.” Osborne considers Tommasini’s review “a real breakthrough.” He also regards it as a piece of virtuoso writing. “As a critic, he kept a dignified tone and yet he lambasted them.” When making his own arguments on the Net, Osborne had bent over backwards to write in sober tones and to offer well-documented notes. “If you want to be responsible, that’s how you must do it,” he insists. “I had to write as though I were producing lab reports.” Despite the push-button ease of the Internet, Osborne’s work was long and lonely. Over the months and years, he gave considerable thought to the strategy and tactics that made for a successful cybergrass campaign. “When you’re picking out somebody to pick on, there are certain rules,” he says. “For instance, I heard of some people trying to get up a protest about the fact that there are so few women band directors in the public schools. Well, how do you protest against 10,000 local school boards? You can’t. “You have to pick out a single institution that’s in the media limelight and has a certain vulnerability.” PERFECT TARGET |

||||

| ‘The Met

hasn’t done an opera by a woman since 1903. There aren’t many around, but

there are enough of them.’ — WILLIAM OSBORNE |

He cites the Metropolitan Opera as a perfect target. “That would get a lot of attention,” Osborne says, “and it would be very useful. The Met hasn’t done an opera by a woman since 1903. There aren’t many around, but there are enough of them. And even if they thought there weren’t any at all, why haven’t they commissioned one? The Met is very vulnerable there.” But although a protest against the Met “would have enormous potential,” he has no intention of taking it on. “It’s a lot of work,” he says, “and it would be better to get somebody who’s a real opera aficianado. I know the inside workings of German-speaking orchestras like the back of my hand. I know what they’re going to say and do before they do it. I don’t know the opera world as well.” Still, if someone were to take on the Met, Osborne emphasizes, the real issue is not the opera itself but the status of women in music. “The Met is just a vivid illustration of how bad things are for women composers. That the major American opera house hasn’t done an opera by a woman during the entire 20th century is worth protesting. Even the major European opera houses have done their token women.” Osborne shakes his head, marveling at such basic and incontrovertible facts. Then he wonders out loud with a Cheshire cat’s smile whether cybergrass against the Met would get any takers. “Maybe somebody will do it,” he says. “I hope so.”• |

Jan Herman is an editor and producer, and theater critic, for MSNBC Living.