|

From the Machines of War to the Body as Compiled Code A review of the ICMC 2000 in Berlin as Published in Music Works

by William Osborne and Abbie Conant The International Computer Music Association is an academic organization comprised of composers, performers, engineers and scientists working to apply digital media to music. The membership is international and the conferences alternate between the Americas, Europe, and Asia. The most recent was held in Berlin from August 27 to September 1, 2000, and included twelve concerts of new music (approximately 70 compositions) and over 130 paper presentations that were also published in the conference’s 563 page “Proceedings.” The conference also produced a CD containing ten of the compositions that were programmed. There were often two to four events running simultaneously, starting at about 9:00 AM and with the last concert of the day ending around 11:00 PM. There was also an Off-ICMC at Berlin’s Podeville that included many additional concerts and a series of workshops. The

opening concert was a rare performance of John Cage’s HPSCHD (one of the

first major computer works) played back through about fifty speakers

laboriously installed in the foyer of the Berliner Philharmonie.

There was a hushed silence as the music began emitting metallic baubles

of defrocked baroque sound from everywhere, but after a few minutes most of

the public, which was standing around in groups, began to talk and continued

to do so through the hour-long performance.

It was a noble effort not fully appreciated by the public. Perhaps

music coming from speakers in foyers has become too ubiquitous.

The

conference included many sessions devoted to “physical modeling.”

The goal is to create software that imitates not only an instrument’s

sound, but also its acoustic principles and performance idiosyncrasies.

This allows the visceral quality of instruments to be playable on

electric keyboards—synthetic clarinets that can imitate the squeaks of reeds

gone awry or the straining air pressure of trumpets that half valve or crack.

Researches at IRCAM have made these models so accurate they are almost

as hard to play as the acoustic instruments they replace.

The next step is to create models for how specific artists play (or

played.) They might, for example, digitally recreate in a robotic sort of way,

some of Coltrane’s mannerisms of playing the sax. There

were eighteen sessions demonstrating concrete results of new research.

Adrian Freed, who works at the Center for New Music and Audio

Technology at the University of California, demonstrated a keyboard that

provides continuous information throughout the entire depression or release of

each key. The device connects to a notebook computer via an Ethernet

connection and among its many uses allows for more expressive and authentic

digital keyboards. Perry Cook and

Colby Leider of Princeton demonstrated two extensively modified accordions

they call “squeezeVoxes” which control physical modeling software with the

instrument’s bellows to synthesize the human voice. Tomoko Yonezawa and Kenji Mase demonstrated a fountain that

played piano music. The speed, range and volume of the music changed in

accordance with the trickle and flow of water through funnels. Researchers

at the University of Zurich and the University of Campinas, Brazil,

demonstrated a robot with a capacity to learn, and then reflect its

experiences in music. It was

programmed to search for spots of light within in a fenced-in area, and

accompany its movement with music. By bumping around it could learn where the

fence was, which made its music low and dissonant, and where bright spots

were, which made its music go up an octave and become more sublime.

The robot, which was about eight centimeters tall, thus had a sort of

ontological and epistemological nature. It’s

learning process created a musical structure that moved from the frustrated to

the transcendent as it learned more about its world and gravitated toward the

light. Epics of human history

passed before your eyes. There

were also displays presenting various projects. One of the most important was

created by Kristine H. Burns, of Florida International University, who

discussed her research concerning on-line teaching techniques and her

“WOW’EM” website. The

beautiful and informative site encourages young people, and especially girls,

to learn more about computer music. Other

areas of research presented included the design of virtual music environments,

movement sensing installations, 3-D sound spatialization, audio encoding

formats, sound processing and perception, transducers and speakers,

intelligent composition tools, tempo tracking software, and sound synthesis

methods. Unfortunately, many of

the presentations were almost incomprehensible, not because the material was

complicated (as it often was,) but because they were poorly presented. One

of the most promising areas of the ICMC were the sessions on the aesthetics of

computer music, organized in part, by Leigh Landy (UK).

In its calls for participation, the ICMC said that, “Computer music

is neither a style nor a genre.”

Two musicologists from Denmark, Ingeborg Okkels and Anders Conrad,

suggested that the ICMC does have an aesthetic bias.

It leans toward “academic computer music” that focuses on abstract

sound created by the latest engineering technologies. Okkels and Anders feel these “engineer composers” are

given preference over other groups, such as those following the American

tradition of experimental music (e.g. John Osterwald and John Zorn) who often use low-tech

instruments such as samplers to collage cultural artifacts. They said that by focusing on tools used, the ICMC declares

tacit aesthetic decisions. It

was apparent that technology is sometimes given more status than musical

quality, and that this occasionally causes composers to “hype” their works

as more technological than they really are.

The technological focus also causes the ICMC to sometimes erase its own

history, since musically valuable low-tech electro-acoustic works are seldom

presented. Karlheinz Stockhausen,

for example, who has left an enormous legacy to electro-acoustic music, was

not presented or present at this conference in Germany.

Okkels and Conrad suggested that the price to be paid for favoring

“engineer composers” is “that the ‘engineer way’, is extending

serial music’s compartmentalization as expert culture” into computer

music. Frederich

Kittler, one of the world’s

most esteemed media historians who is a professor at Humbolt University in Berlin,

discussed the relationship between technology

and war. He expressed his belief

that computer music derives from the same cultural milieu as the “men in

white coats” who work for the military-industrial complex. He suggested that for our own well being we must learn more

about the social meanings of technology and the “ontology of thinking

machines.” Natasha

Barrett, a Brit living in Norway, illustrated her methods for basing

compositional structures on mathematical models of natural phenomena such as of

avalanches or the spatio-temporal distribution of animal vocalizations in

tropical rainforests. Barry Truax,

by contrast, spoke of the computer’s ability to represent and create forms

of internal drama. Since computer

music allows for such precise control of sound and requires no performers, it

naturally leads to an internal world that is very real, only real, as opposed

to the “hype” of virtual 3-D realities where we always remember there is

a computer somewhere in the background. Even

though five of the nine papers on aesthetics were by women, there were none on

the final grand panel comprised of six sagely male professors. Whatever the future of computer music might be, it appears

women are being partially left out. Only

40 of the ICMA’s 499 members are women—or 8 percent. Interestingly, 17 percent of the compositions presented at

the conference (which were selected by anonymous submission from over 600

applicants) were by women--over double their membership in the

organization. It

is not possible to review all seventy compositions presented, so we can

provide only a small representative cross-section.

There were two categories of works, those using only electro-acoustic

sound, and those using electronics with soloists or small chamber groups.

It seemed that about two thirds of the works used “tapes,” and

about one third used some form of live “interactive” electronics--usually

involving the programs MAX or SuperCollider.

The

two concert spaces, the Matthäus church and the Akademie der Kunst, had excellent

octophonic sound systems installed in them.

Due to the aesthetic focus of the programming, there were no

presentations involving ensembles of electronic instruments, and very few

works dealt even remotely with discrete pitch divisions and forms of metrical

rhythm. Timbreal manipulation of

sound was the focus. There were,

in fact, a number of composers with scientific or engineering backgrounds who

did not have extensive “formal” musical educations. Todor

Todoroff’s “Voices Part II” (Belgium) evoked his childhood memories of

building and listening to small radios. Delicate sinusoidal glisses recalled old

radios being tuned, while ghostly, staticy voices built to very powerful low

square waves. Marc Ainger’s

“Shatter” (USA) impressed by emulating shattering glass and metal objects

accompanied by the sounds of heavy machinery.

Cort

Lippe’s “Music for Hi-Hat and Computer” (USA) was one of the most

effective “interactive” works of the conference.

Due to the cymbal’s rich and extensive overtones it can be filtered

to great effect. This allowed the cymbal to be sampled, time streched, and

modulated timbreally and spatially in many variations by a program in MAX/MSP. The work had an improvisatory character and was a bit

repetitive toward the end. Richard

Karpen’s “Sotto/Sopra (USA) was an interactive work for violin and

computer using similar technologies and was notable for its fine violin

writing excellently performed by Iliana Göbel. Christopher

Dobrian’s “Entropy” (USA), written for Diskklavier and video projection,

stood out because it was one of the few works to exclusively use a set of

twelve pitches with no timbreal alterations.

MAX patches created fascinatingly inhuman gestures sweeping across the

keyboard. Gordon Monroe’s

“The Voice of the Phoenix” (Australia) for tape and contrabass flute,

which rises from a peg on the floor and stands over six feet tall before

bending back to the performers mouth via a huge triangle, was interesting

because the acoustic instrument was far more exotic than the electronic sounds

surrounding it. Monroe, a

professor of mathematics, writes sophisticated music, even though he mentioned

in conversation, perhaps with an excess of modesty, that he wouldn’t know

how to resolve a diminished 7th chord.

Composer,

Ludiger Brümmer, and video artist, Silke Brämer, (both from Germany)

presented a well-received and highly compelling work for video projection and

loudspeaker using software that correlates the creation of sound and video

images. Francis Duhmot (Canada)

presented one of the best works of the conference.

Based on samples of various types of flutes, it stood out due to its

extremely well crafted structure unifying an interesting variety of subtlety

worked material, a fine sense of tension and release, excellently spatialized

by the composer at the mixer. The

ICMA made no error in offerings its conference commission to Elizabeth Hoffman

(USA.) Her stunning work in four

continuous movements, entitled “Mannhattan Breakdown,” for clarinet,

cello, percussion, tape and live electronics, explored improvisatory

structures based on predetermined elements and used a free temporal

interrelation between the live performance and tape. Her work demonstrated a

wide-ranging command of compositional methods. Toward

the end of the conference, the music began to become rather predictable due to

the aesthetic confines of the festival’s programming scheme. The homogeneity

also existed because so many people were using relatively similar synthesis

programs—especially MAX and SuperCollider.

These programs are very flexible, but composing with “patches” can

create aesthetic and epistemological biases that incline music toward certain

kinds of sounds and effects. Washes

of sonic material made by stuttering loops of granulated sound shaped by

glissing

modulated timbre were ubiquitous, as were improvised, real-time

spatializations at the mixing board. If

there was a general weakness to the music, it was structure. Timbreal studies are new to western music and so there are

few models for structuring them. After

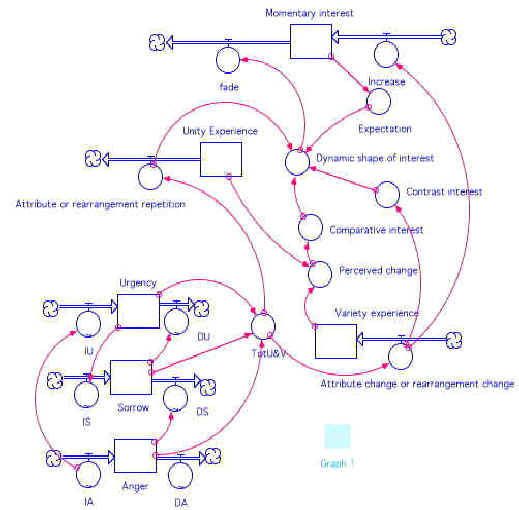

observing this problem in previous conferences, Ian Whalley (New Zealand)

presented a paper suggesting that system dynamics modeling might be used to

create narrative structures for computer music. He demonstrated the idea with

computerized flow charts outlining the structures of works such as

Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

(See diagram below.)

Problems remain though, because one still needs something semiological (signs and signifiers with metaphorical meanings) to place in the structures. Timbre, which seems to be the focus of much computer music, might not have the same richness of semiological meanings associated with it as pitch and rhythm. The reasons for this might not be only cultural, but also have something to do with the kinesthetic characteristics of music.

If

there was any single impression left by the conference, it is the extent to

which the computer is disembodying music.

In his keynote address, Joel Chadabe, said, “We want a holistic

instrument that stresses the intellect and isn’t dependant on the body. We

can play the sounds of a cityscape. Why

do you need a body for that?” Even

though he is not against the body, he spoke of it as an unnecessary hindrance

to music-making, a limitation to freedoms of the intellect.

Some feel this approach might be based on false assumptions about what humans are. In the last two decades, cognitive psychologists such as George Lakoff have argued that there is no Cartesian dualistic person with a mind separate and independent of the body. Reason is not disembodied. Its very structure comes from the details of our embodiment. Philosophers such as John Dewey and Merleau-Ponty, also view the body as inseparable from reason, the primal basis that shapes everything we can mean, think, know, and communicate. We may find that there is no quick path to putting the body in music, and that without the long, existential process of making an instrument and the body-mind one, we weaken cognitive structures that are essential to musical meaning. Technical and aesthetic strategies for solving this problem formulate the future of computer music.

|