Aletheia

2. Score

3. Text

4. A Slide Show

5. Trailer

6. Video

7. Review of the Avant-priemere

8. Syopsis

10. Goals

11. Keyboard Howls

12. Tour Itinerary

![]()

1. General

Description

Alethea was premiered for the International Trombone Festival on Friday, June 30, 2017

at the University of the Redlands near Los Angeles, California. A

preview was presented at the University of Music in Trossingen, Germany

on January 10, 2016.

“Aletheia is getting

ready to sing for some arts patrons in the courtyard below. She sings

about the magic of words, the Logos, that allows words to create

reality. At first, she just wants the magic of words to make her young

again, hemoglobin grammar as she calls it, like a spirit that comes with

the wind. She thinks about the wealthy patrons below, about the

plutocracy and phoniness of the arts world. Slowly she begins to realize

that the magic of words, the magic of art, might do something far

greater than make her young again, that they might revive the dying city

in which she lives. If only the patrons of neglect and the patricians of

rot would allow those words to be heard. She wonders how her voice might

transcend the cage in which she’s imprisoned, how she might raise her

voice on the winds of time.

Text and

Performance: Abbie Conant, trombonist, singer, actress

Composition, Text, Direction, Sound Design,

Stage Set: William Osborne

![]()

2. PDF Score

To download a PDF score of Aletheia click here. The latest version of the score is February 20, 2017.

![]()

3. Text

To download a PDF copy of the text click here. The latest version of the text is February 20, 2017.

![]()

4. Slide Show

![]()

5. Trailer

In progress.

![]()

6. The complete video of Aletheia

![]()

7. Review of the Avant-premiere

Trossingen Zeitung, January 12, 2017

Opera Singer in An Iron Cage

Abbie Conant unites acting, singing, and trombone in one person

by Jutta Bärsch.

A professor’s concert was announced for Tuesday evening at the University of Music in Trossingen. The hour long offering captivated and convinced through the unity of acting, singing and trombone-playing in one person.

The renowned American trombonist and performance artist Abbie Conant showed that new, experimental music can sound melodic. The vocal material consisted mostly of recitatives, embedded in the sounds of a computer-controlled piano and quadrophonic electronics.

Multimedial Performance

Abbie Conant developed this multimedia performance together with the composer William Osborne, whose music at some points recalled the recitatives in Eugene d'Albert's opera "Tiefland". Osborne was responsible for the stage direction and sound design.

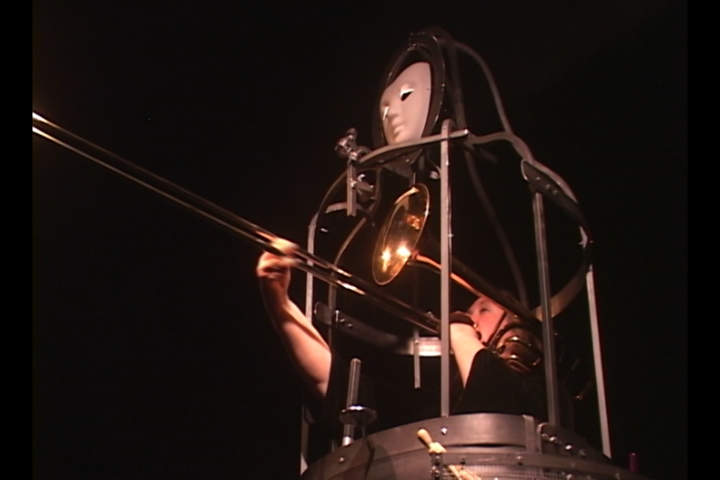

In

a brightly lit cage on an otherwise black stage, she portrays an opera singer,

Aletheia, who is really looking forward to her performance at a prestigious

gala for the "establishment’s" rich opera lovers.

But during her preparations she begins to doubt: does she not know she lives in a cage, in a cage in the form of an iron maiden?

She begins to sense how wrong the world really is, that "her" wonderful opera house in Detroit stands in a city that is only a shadow of its former glory due to the decline of the automobile industry, and is actually in ruins.

The Suspense Remains

Aletheia

begins to ask existential questions, a women's choir that seems to float above

her answers her. Or is it just a dream? She hears distant melodies from

"Madame Butterfly."

In the end her trombone playing and the piano blend with the sphere of the surround-sound electronic soundscapes.

Thanks to the detailed program, the performance sung in English was quite understandable. Abbie Conant was able to stand in this cage for 60 minutes, sing, play trombone, and act without losing the suspense even for a second.

A virtuosic achievement by the protagonist and a great performance that presented experimental music in a tonal soundscape.

See

the article on the Trossingen Zeitung Website

here.

![]()

8. Synopsis

Aletheia is excited as she prepares to sing

for an opera gala in the courtyard below her window. She feels words are

a form of magic, and that if she finds the right ones they will keep her

forever young.

She sometimes touches the mask above her head

and sings fragments of a song about the magic of theater, “Follow me my

light as I walk the ways of blood…” There seems to be soft ghost voices

in the piano that accompanies her.

She

looks out the window to describe the guests in the courtyard below. She

tries to reach her lover Jeremy with her cell phone but he does not

answer. She feels the breeze from the window and hopes it will raise her

song to the sky.

She

looks out the window to describe the guests in the courtyard below. She

tries to reach her lover Jeremy with her cell phone but he does not

answer. She feels the breeze from the window and hopes it will raise her

song to the sky.

She recalls that the gala below is only for rich people, and wonders if they would even notice if she did not show up.

She sings about how our ballads dream us into being, each word etching a scene. She says dreams fall into other dreams, and tells of one where a shark ripped her body in two, “As I watched fading into death, liquid smoke of my own screams, rusty red garlanding all around me. I see each word sticky and reddish, hemoglobin grammar.”

She wonders why she is having trouble going down to sing. Is it the people, the music, her lack of courage? “Music it seems has become a bit hard of hearing, it shuffles around like a ghost in an old opera house.”

She hopes her trombone might help and begins playing it, “something for opulent patrons with nothing ambiguous in their lives, except of course, their financial transactions.” Her frenetic playing is a pastiche of fragments, “but what can we say in a world so completely unhinged.” The times are too dangerous, “So I’ll continue with something abstract, with nary a word of protest, or they take our funding away.”

She puts her trombone away and vows that she will sing unscripted truths, that she will hallow this very room with her song.

![]()

9. The Troubled History of Opera In the USA

There are many

metaphorical levels to Aletheia. One of the most basic is the neglect of

the arts in the USA. The country, for example, once had a lively opera culture but after about 1930, it gradually became marginalized and

neglected. There were big opera houses, but they were systematically

destroyed by economic policies, and their legacy largely lost from

memory.

According to Operabase (when it still had

comprehensive statistics,) the USA ranks 39th in the world for opera

performances per capita, behind every European country except

impoverished Portugal. The USA only has three cities in the top 100 for

opera performances per year. Germany has 83 full time opera houses,while the USA only has one, the Metropolitan Opera. The next

two largest companies, Chicago and San Francisco, only have half year

seasons—something unthinkable for European cities that size.

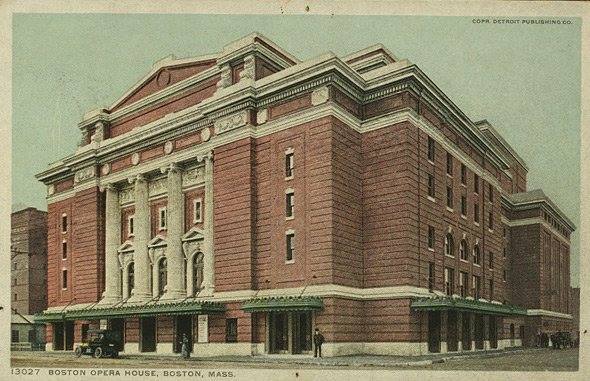

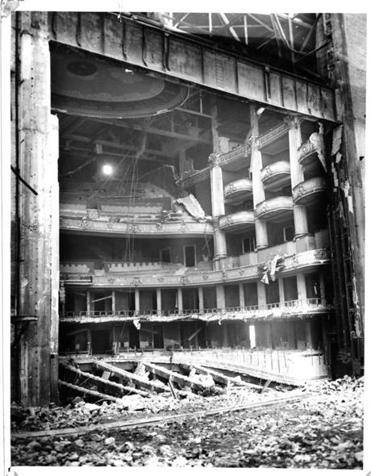

From about 1930 to 1960, many opera houses

were destroyed after falling into neglect. The magnificent Boston Opera

House opened in 1909 and was demolished in 1958 to create a parking lot.

Its acoustics were said to be excellent. The building was so solid that

three different demolition companies were hired before one could do the

job. Here are some photos of the original opera house's exterior, one of

its interior, one of it as a ruin, and one of the renovated movie

theater now called the Citizens Bank Opera House.

|

|

|

|

In 1980, Boston’s small opera company moved into the repurposed movie theater that was given the name, Citizens Bank Opera House, but the company closed in 1990 due to financial problems. The house reopened in 2004 but is used mostly for the Boston Ballet, popular entertainment, and a venue for video game competitions. According to the last stats posted on Operabase, Boston now ranks 250th in the world for opera performances per year.

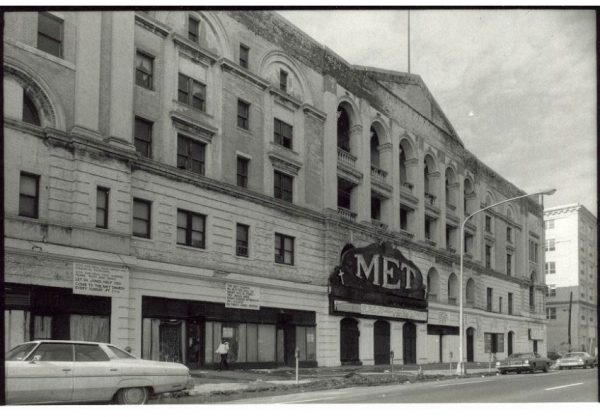

The Philadelphia Metropolitan Opera House has a similar history. It was built in 1908 and ceased operations in 1934. For the next 50 years it gradually fell to ruin and was intermittently used as a movie theater, ballroom, sports venue, mechanic training center, and church. In 2017, it was renovated by Live Nation Philadelphia for popular entertainment. Here are two photos of the Philadelphia Met in its heyday, one of it abandoned, one of it under renovation, and one of how it looks now as a popular entertainment venue..

|

|

|

|

|

The consequences of this neglect are obvious. According to the last stats on Operabase, Philadelphia ranks 109th for opera performances per year even though it has the 9th largest metro GDP in the world. They no longer use the opera house. The company’s productions are usually low budget with short runs done in often ill-suited rental facilities with pickup musicians. On the positive side, they approach these problems with creative verve and use them as a source of innovation.

The Philadelphia suburban area known as the Mainline has one of the largest concentrations of wealth on the planet while the city has some of the largest and most dehumanizing ghettos in the country. And worse, the ghettos are based on a racial class system. The city has the highest number of people living in deep poverty in the USA, including 60,000 children. Under the USA’s form of unmitigated capitalism, the neglect of cities and people can clearly be correlated with the neglect of the arts.

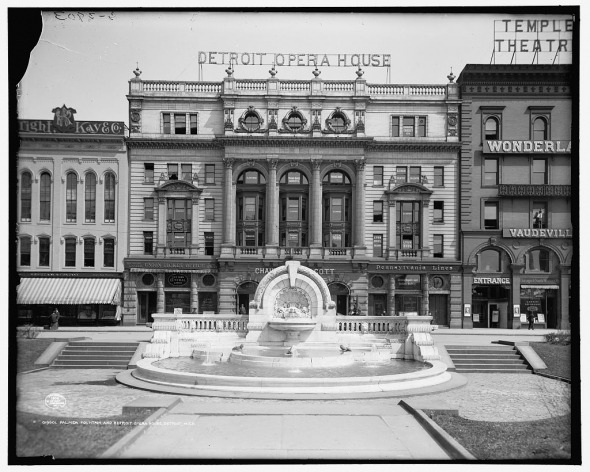

Detroit tells the same story. The original Detroit Opera House was built in 1868, destroyed by fire in 1897, and quickly rebuilt in less than a year. In 1931, it ceased operations and became a movie theater which also hosted burlesque shows and church services. In 1935, it was gutted and turned into a cut rate department store. In 1966, the building was demolished.

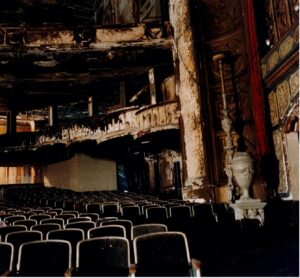

Today, as in Boston, Detroit's opera company, Michicgan Opera, works in a renovated movie theater. Here is a photo of the origianl opera house, two photos of the movie theater before its renovation, and a photo after the renovation. As in most US cities, there are few opera performances, so the venue is most often used for other purposes.

|

|

|

|

The movie theater renovated in Detiort had gone into steady decline as the city around it collapsed. It closed in 1978 after surviving several years exhibiting second-run and soft-core porn films. It briefly reopened again in 1981 but closed after a minor fire in 1985. Despite its troubles, Detroit still has the 24th largest metro GDP in the world but ranks 263rd for opera performances per year. This low number is normative for larger American cities. Opera is thus only a small part of its useage.

Nevertheless, the renovated theater has revived its Detorit neighborhood. The Michigan Opera recently received a $5 million grant, the largest in its history, but it should noted that the budget for the state opera companies in European cities the size of Detroit are usually in the range of $150 million. With extensive educational programs and affordable tickets, they create large publics, do many more productions and performances, and give their artists far more financial security and respect.

Europeans also enjoy genuine opera houses whose sight lines, acoustics, workshops, orchestra pits, lighting bays, and storage spaces are often better suited for opera than renovated movie theaters.

Americans often react resentfully when this history and these comparisons are mentioned. They frequently attempt to rationalize a form of American exceptionalism that often leaves their cultural lives impoverished and large areas of their cities in ruins.

There are no greater heroes than the people working to revivie and sustain opera in the USA. In many respects, our work Alethiea is an expression of support and compassion for what they do.

A second level of irony in the metaphors of Aletheia is that for the last 25 years we have not been able to perform in Germany’s massive system of state theaters and festivals even though we have lived here for 41 years. We are ostracized due to our activism against sexism in the country’s arts world, a situation made even more complex because we are foreigners. (The listing of our performances shows the change after 1994 when we began to speak out.) This is another aspect of how artists can be caged.

![]()

10. Goals

Some of our goals during our 40 years of work in music theater:

1. Establish chamber music theater as part of the mainstream repertoire.

2. Move music theater away from 19th century melodrama to modern theatrical theory, smaller, black box theater, existentialism, more philosophically complex.

3. Through-composed music theater with topics, lengths, and pacing that correspond to the modern world.

4. Music theater with genuine characters and character development combined with

dramatic substance that allows for genuine, multidiminsional acting.

5. Give music, text, and acting all equal importance.

6. A form of singing that allows the words to be easily understood.

7. Works where the words and music are created by the same person, and where they are so deeply integrated that the authorship of the text is part of the compositional process.

8. Composers and performers versed in theatrical theory, theater history, stage lighting, stage direction, videography, Klangregie, computer music, and writing music theater texts.

9. Multi-disciplinary performers adept at singing, playing an instrument, acting, dance, mask work, clowning, and pantomime.

10. Chamber music theater scores with so much theatrical detail that they function as production books.

11. Music theater adapted to modern economic concepts, and long processes of revision and experimentation.

12. Music theater that uses modern media, such a computers, video, and surround sound.

13. Documentation our theories of chamber music theater with performances and videos.

![]()

11. Keyboard Howls

Many people have heard

of the term “orchestral operas,” like those written by Wagner, where the

orchestra plays an especially central role.

With Aletheia, we have tried to explore the idea of a “piano opera” --

the idea that the sounds of a piano are so complex and rich that they can

narrate a story and bring a character to life.

In most of our works, we set the voice clearly above the accompaniment,

but with Aletheia we have tried to immerse the voice in the piano as if

Aletheia herself is a ghost that rises out of the hidden sonorities of its

strings.

For those with the ears

and minds to hear them, the notes of pianos are full of ghosts.

Each piano hammer and string is different, as is every tuning and every

attack and damper movement. A

world of unique overtones and interferences rise out of each note.

Each one howls and shimmers and cries in a different way, further

amplified by the uniqueness of every sound board. And those ghostly keyboard

howls have a dialog with the acoustic ghosts that exist in every room.

For those with the ears

and minds to hear them, the notes of pianos are full of ghosts.

Each piano hammer and string is different, as is every tuning and every

attack and damper movement. A

world of unique overtones and interferences rise out of each note.

Each one howls and shimmers and cries in a different way, further

amplified by the uniqueness of every sound board. And those ghostly keyboard

howls have a dialog with the acoustic ghosts that exist in every room.

Much of this effect is

lost on digital pianos, so when I composed Aletheia I tried to find those

cousin ghosts that exist in the electronic world -- sounds produced by similar

overtones, resonances, and interferences.

I then occasionally placed them along with some of the piano notes with

an almost imperceptible softness so that ghost sounds weave in and out of an

underworld between the piano’s notes.

The ghosts are often almost invisible, but sometimes they become

clearly audible. And as the work

reaches its climatic points, the ghosts sometimes leave the shadows completely

and roar into the forefront of the sonic world.

In the same way,

Aletheia’s being is also a ghost rising out of the piano.

To our minds, and in our musical world, we think of Robert Schumann as

one of the spirits behind this work.

He was especially adept at writing music for the piano that seemed to

derive in part from the ghosts in the strings.

We even picture him in his asylum, very sober of mind, playing the

piano in a timeless and immaterial world where the being of Aletheia rises out

of the strings and hovers above the instrument to tell her story about opera

galas and the patrons of neglect in the ruins of Detroit.

The ghosts in piano strings become an invocation, a form of magic that

brings a world to life, a gentle breeze that she hopes will raise her voice to

the sky.

In the same way,

Aletheia’s being is also a ghost rising out of the piano.

To our minds, and in our musical world, we think of Robert Schumann as

one of the spirits behind this work.

He was especially adept at writing music for the piano that seemed to

derive in part from the ghosts in the strings.

We even picture him in his asylum, very sober of mind, playing the

piano in a timeless and immaterial world where the being of Aletheia rises out

of the strings and hovers above the instrument to tell her story about opera

galas and the patrons of neglect in the ruins of Detroit.

The ghosts in piano strings become an invocation, a form of magic that

brings a world to life, a gentle breeze that she hopes will raise her voice to

the sky.

This is, of course, an insane idea, but maybe a little less so for those who hear the ghosts in the notes of pianos, the keyboard howls, the spectral world of the piano’s specters, the ephemeral operas in Robert and Clara’s ghost minds.

It is in the mysteries of resonance that the space is created where the ghosts of the piano can materialize. Similarly, altheia is one of several ancient Greek words for truth that roughly means "to create a space where truth can appear." Aletheia is in search of that space in a debased society, a world where she hopes there is a space for the ghostly whispers of transcendent truth, a resonance that will bring her freedom.

![]()

12. During the 2017-2018 season, we performed Aletheia in 28 cities. We performed it in another 7 in 2020, and 9 more were cancelled due to the pandemic. Click here to see the itinerary and photos of our university residencies that were part of these tours.